The Best Delegate Election Process for a New York Constitutional Convention

NYS Assembly chamber (photo: MattWade on flickr)

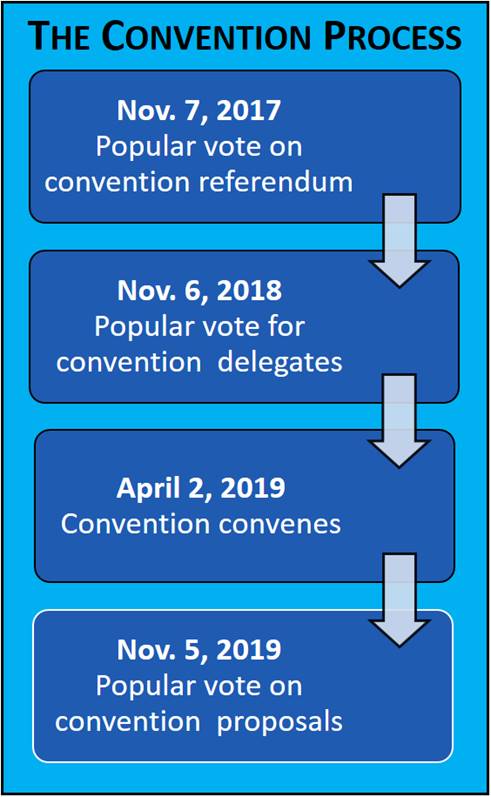

On November 7, 2017, New Yorkers will be asked to vote on whether to call a state constitutional convention. When this question was last on the ballot in 1997 (it’s required to be on the ballot once every 20 years), the most publicized argument not to call a convention was that the convention delegate election process would be dominated by the same interests that dominate New York’s Legislature.

That argument fails to account for the many successes of America’s 236 state constitutional conventions since 1776, including New York’s nine. It also fails to explain why the same special interest groups who would supposedly benefit from a convention will spend millions of dollars opposing one. Except for the fact that incumbent public officials can run as delegates, New York has one of the best delegate election processes among the states.

But, there is still much room for improvement.

New York’s Delegate Election Process

New York’s Constitution mandates what’s known as a mixed delegate election system. Of the 204 delegates to be elected, 189 are elected from New York’s 63 state Senate districts (three from each district) and 15 elected at large for the entire state. Crucially, the details of how this mixed system works are left up to the discretion of the Legislature.

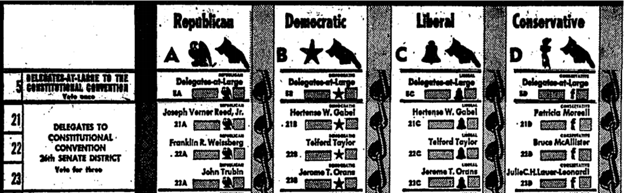

The last time the Legislature chose the election details it created a system whereby in each Senate district voters voted up or down for three candidates, and in the at-large election voted up or down for a party-based slate of candidates (see the sample ballot below).

A Better Delegate Election Process

A better mixed system would be built on a foundation of what political scientists call Mixed Member Proportional (MMP), a type of electoral system used in Germany and New Zealand at the national level; and Scotland, Wales, and more than a dozen German states at the regional level. In a 2006 survey, political scientists who specialize in electoral systems ranked MMP as the best family of electoral systems.

Part of the MMP mix would include ranked-choice voting, a type of electoral system used in Ireland and Australia at the national level, and in many U.S. cities at the local level. In 2016, Maine voters approved a ballot initiative to choose the Governor and state Legislature via ranked-choice voting. In the same 2006 survey, ranked-choice voting was ranked the second-best family of electoral systems.

In an MMP system, voters cast two types of votes: one for candidates in their local district, and one for a party. The votes, in turn, count for two tiers of seats: a local candidate tier, and a compensatory tier for parties that didn’t win seats in the candidate vote in proportion to their party vote. Within the constraints of New York’s current constitution, this could work as follows:

In choosing candidates from their local three-member Senate district, voters would rank their preferences rather than vote up or down for each candidate. Such a “ranked-choice” voting system wouldn’t require separate primary and general elections because runoffs are instant. Most important, it wouldn’t penalize voters for voting for their first choice rather than a less preferred candidate with a better chance of winning. With New York’s three-member districts, any district candidate with 25% of the vote plus one would win a district seat, thus strengthening party competition and mitigating the harmful effects of partisan gerrymandering.

The party votes would be used to ensure that the ratio of seats to votes is proportional. For example, assume the Democratic Party gets 49% of the vote, the Republican Party 46%, and an independent party 5%. Under the current delegate election system, the Democratic and Republican parties would most likely win 100% of the seats. But under MMP, the independent party would be entitled to 5% of the overall seats and thus win ten of the fifteen at-large seats, with the balance divided proportionately among the Democrats and Republicans. The result of such compensatory seats is that small parties and political entrepreneurs would have a much greater incentive to compete in the election.

Each party would compile its list of candidates for proportional allocation the way it wanted. For example, a party could add the proportion of a candidate’s district vote (e.g. the number of top-three votes) to the proportion of the party’s district vote to come up with a candidate’s party list ranking. Many other methods could also be used.

When a delegate’s seat became vacant, the party would choose the next name on its list as a replacement. No special election would be held.

Although the 15 at-large, compensatory seats might seem to guarantee a relatively small amount of proportionality, the combination of ranked-choice voting in the three-member districts plus the compensatory seats would lead to a remarkably high degree of proportionality (although having more compensatory seats would be even better).

A state-of-the-art electoral system should provide not only voters, but also parties and candidates, with more options consistent with the principle of political equality and robust public deliberation. Mixed Member Proportional (MMP) combined with ranked-choice voting accomplishes that.

Party-Based Electoral Competition is Good

In the United States, the media teaches the public to think disdainfully of political parties. Consequently, the word “partisan” has become a dirty word. But contemporary democracy is unthinkable without parties, and party labels are an extremely efficient and effective system for educating the public about candidates. MMP offers the best of both party- and candidate-centered elections while radically diminishing the need for public financing of elections.

States have had many democracy enhancing constitutional conventions that were dominated by two-party delegate competition, including New York’s famous state ratifying convention in 1788 that was dominated by Federalists and Anti-Federalists (the Anti-Federalists won the most delegate seats but were eventually convinced to side with the Federalists). The chief worry should not be party but incumbent legislator dominated conventions. Only the latter type of domination violates the core democratic function of a convention, which is to bypass the Legislature’s gatekeeping power over constitutional amendment. Still, using MMP to lower barriers to entry for both parties and candidates would greatly strengthen the delegate election process by providing voters with more meaningful choices.

New York’s past practice of having candidates outside the two major parties run as a slate is a vastly inferior alternative to MMP but probably the best that New York’s Legislature would allow if voters approved calling a convention. Thus, reform groups may focus their efforts on putting together a slate. In 1966, when New York last had a delegate election, such efforts were remarkably successful—albeit still inadequate (7% of the elected delegates were incumbent legislators).

Getting to MMP

Getting to MMP

The politics of improving the delegate election process are admittedly dismal. Legislatures hate conventions because they function as a check on their power, so the last thing they want to do is strengthen the institution. Ditto for the powerful special interest groups that thrive working through the Legislature and thus view a convention as a threat.

One reason for hope is that federal courts could rule that the delegate election system approved by the Legislature for the three-member districts violates the proportional requirements under Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act. The 1965 Voting Rights Act was passed just before the last delegate election took place in 1966. If the Legislature doesn’t change the type of system it approved in early 1966, it is likely to be sued under that law. That could give the federal courts the ability to design a more proportional electoral system such as single-member districts (the courts’ conventional remedy based on using an up-or-down voting rule) or ranked-choice voting within the constraints of New York’s constitutionally specified three-member districts.

The best long-term hope for meaningful delegate election reform is the political logic of the famous “veil of ignorance” effect regarding democratic reforms that won’t take effect for at least 20 years into the future. The basic idea is that even crassly self-interested convention delegates would have an incentive to support democracy enhancing reforms such as MMP if they wouldn’t take effect until after those delegates would be retired from politics and couldn’t foresee how they would personally benefit from preserving an otherwise inferior status quo.

Most of those using the delegate election process as an argument against calling a convention are using that argument as a pretext for opposition on other grounds. But they do have a point, so those who aren’t using that argument as a pretext should direct their energies to fixing the process either through the Legislature and courts or, if that’s not possible, the next convention.

The U.S. Declaration of Independence asserts that Americans should have an “unalienable” right to “alter” their form of government, including the right to peaceably bypass their legislatures’ gatekeeping power over needed democratic reforms. The inter-generational struggle to protect and enhance this most fundamental of all democratic rights should dwarf considerations of short-term expediency. The cure for the deficiencies of the current process, like democracy itself, is a better process, not the eternal tyranny of the legislature over the constitutional amendment process.

Like all electoral systems, a Mixed Member Proportional (MMP) system with ranked-choice voting is not perfect. But to safeguard our most fundamental of all democratic rights, it would be a great legacy for us to leave to future generations of New Yorkers.

***

J.H. Snider, the president of iSolon.org, is the editor of both The State Constitutional Convention Clearinghouse and The New York State Constitutional Convention Clearinghouse.

#

Source: Snider, J.H., The Best Delegate Election Process for a New York Constitutional Convention, Gotham Gazette, November 17, 2016.