Needed: Fresh Eyes to Improve New York’s Constitution–Part 1

This is part one of a two-part series entitled Needed: Fresh Eyes to Improve New York’s Constitution. Read part two here.

New York’s Mandarin Constitutional Culture

(photo: Samar Khurshid/Gotham Gazette)

During the last 500 years, a culture of innovation set off the West from the rest of the world, allowing it to achieve far higher living standards. Incentives for innovation have remained strong in the private sector but have greatly weakened in the public sector.

The United States and its most innovative state, New York, have led the West in innovation. During the 18th and 19th centuries, this included leading the world in constitutional innovation, which is arguably the most important type of public sector innovation. But present-day New Yorkers and their opinion leaders are as allergic to such innovation as Chinese emperors and Mandarins were in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Symbolic of the decline are the stale ideas currently dominating New York’s debate over whether to call a state constitutional convention. Every 20 years the state constitution mandates that New York voters be asked whether they want to convene another state constitutional convention. To date, New York has convened nine proposing and two ratifying conventions. On November 7, 2017, this question is next on the ballot.

The unique democratic function of a state constitutional convention is to provide a mechanism to bypass the state Legislature’s veto power over constitutional amendment when the Legislature’s institutional interests conflict with those of the public. The result is that not only the Legislature but also the most powerful special interest groups that thrive exercising influence over the Legislature are implacable enemies of state constitutional conventions.

The current debate in New York has been dominated by opinion leaders who were already adults when New York’s last constitutional convention convened in 1967. They have much to bring to the current debate, especially a sense of history, and we are lucky to have them. But too often their and their allies’ reform ideas are from a different generation. Their ideas may be improvements over the antiquated status quo, but so were the now obsolete audio and video tape recorders from the second half of the 20th Century that replaced paper-based recording technologies.

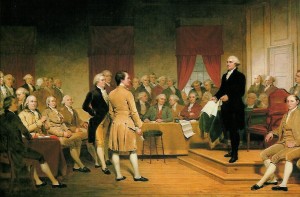

In contrast, when Thomas Jefferson wrote the U.S. Declaration of Independence and when James Madison and Alexander Hamilton both participated at the 1787 national constitutional convention and then defended it in the Federalist Papers, they were all under 40 years of age. The three leading figures behind the design of New York’s first constitution in 1777 — Gouverneur Morris, Robert Livingston, and John Jay — were all 30 years of age or younger. They brought to the design of our federal and state governments fresh eyes and many innovations from which we have greatly benefited.

A better balance between the old and new is needed. Unfortunately, getting true innovators involved in democratic reform is one of the hardest parts of democratic reform, as the rewards for such innovation are often negligible at best. Consider just one reason: why do the immensely difficult and costly work of developing an innovation that has no chance of being implemented because of a legislature’s institutional conflict of interest?

A state constitutional convention is one of the few institutional mechanisms in our democracy with the potential to stimulate fresh thinking. It would be a tragedy to squander that opportunity.

My greatest worry is not, as convention opponents argue, that special interests will derail a convention by getting it to place harmful proposals on the ballot. If special interests do corrupt a convention—and they will certainly try—the people have shown they can be trusted to veto the resulting proposals. This, after all, is why New York’s and other states’ most powerful special interests hate the institution of the state constitutional convention and have spent so much to oppose convening one: they are more confident in their typical, ongoing control over legislatures.

A greater worry should be that New York’s opinion leaders, including its press, academics, advocates, and politicians, will continue to treat democratic innovators the way Chinese Mandarins did during the era when the United States was founded. New York needs to breed a new generation of Alexander Hamiltons, and the time to begin that effort is now.

New York, despite its vast human and material wealth, has become too much like 18th century China, when China was a vastly larger, more sophisticated, and more prosperous country than ours but became arrogant and thus complacent in its superiority. New Yorkers should look to democracies, including Estonia, Iceland, and Sweden—two of them about the size of New York when it drafted its first constitution—where a can-do culture of democratic innovation survives.

New York, like China thought it was for hundreds of years, remains at the center of the world. But it won’t remain there unless it proves capable of developing an outward looking culture characterized by both constitutional humility and innovation.

***

This is part one of a two-part series entitled Needed: Fresh Eyes to Improve New York’s Constitution. Read part two: Implementing First Amendment Values in the 21st Century. And, read other columns by J.H. Snider here.

***

J.H. Snider, the president of iSolon.org, is the editor of The New York State Constitutional Convention Clearinghouse and author of Does the World Really Belong to the Living? The Decline of the Constitutional Convention in New York and Other US States, 1776–2015.