Opportunity for Reform: Educate New Yorkers on constitutional convention

On Nov. 7, New Yorkers will be asked whether they want to call a state constitutional convention. New York’s Constitution mandates that every 20 years this question be placed on the ballot. Based on the recent history of New York and other states, New Yorkers will most likely vote no.

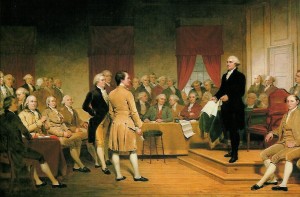

New York’s constitutional convention process grants the people three sets of votes: to call a convention, to elect delegates to a convention, and to vote convention proposals up or down. The unique democratic function of this process is to provide the people with a mechanism to bypass the state Legislature’s veto power over constitutional amendments. Ordinarily, this veto power doesn’t hinder needed constitutional amendments. An exception occurs when a legislature’s and people’s interests conflict, including issues involving a legislature’s internal powers (e.g., legislative term limits, redistricting, ethics, transparency, and ballot access) and competing branches of government (e.g., judicial, executive, and local).

Never in U.S. or New York state history has there been such an extended drought in calling state constitutional conventions. Since 1776, the United States has convened 236 such conventions but none during the last 25 years; New York state has convened nine but none during the last 50 years.

In an article published in the Journal of American Political Thought, I explain this decline in terms of three long-term political forces:

• Legislature opposition has increased: Since a convention checks a legislature’s powers, legislatures intrinsically oppose them. But this opposition has increased, partly because of the rise of career-oriented incumbent legislators with their greater incentive than citizen legislators to oppose democratic reforms that might weaken their incumbency advantage. For example, Jeffrey Stonecash calculates that New York legislative turnover dropped from 67.3 percent in the 1870s to 10.2 percent in the 1980s.

• Special interest group opposition has increased: Successful special interests, especially unpopular ones in heavily regulated industries, prefer to exercise influence through a legislature rather than a constitutional convention, where their legislative allies cannot veto reform proposals. Consider the evolution of Big Labor in New York. When in the early 20th century it was popular but couldn’t get what it wanted from the Legislature, it championed conventions such as New York’s 1938 convention, where it won the pension protections it now fears losing. Since the 1980s, the political dynamics have reversed, with Big Labor, especially government unions, taking the lead in organizing and financing convention opposition.

• Public ignorance of the state constitutional convention has increased: This makes it easier for legislators and special interest groups to paint a convention as a wasteful Pandora’s box controlled by the very political actors it was designed to check. This ignorance has grown partly because students don’t learn about state constitutional conventions in school and adults no longer have any direct experience with one. Nowadays, less than half of New Yorkers even know they have a state constitution.

Given its vital democratic function, the state constitutional convention’s decline has become symptomatic of democratic decline. But countervailing political forces do exist, including New Yorkers’ growing disgust of Albany and mistrust of Albany’s capacity to reform itself.

If the experience of other states in recent decades is a reliable guide, convention opponents will come out of the woodwork in the weeks and days before the referendum. Their campaign will be orchestrated in the shadows under the direction of some of the most accomplished political operatives in America and with a budget dwarfing convention proponents.

In preparation for this onslaught, opinion leaders should provide New Yorkers with a sense of the special purpose, history, and politics of this institution in not only New York but other states. Given the current level of ignorance about this institution, this is a daunting task. But given that this institution protects a core democratic right, arguably the most fundamental of all political rights — the sovereign people’s right to reform their government — it is a task well worth undertaking.

***

J.H. Snider is the author of Does the World Really Belong to the Living? The Decline of the Constitutional Convention in New York and Other US States, 1776–2015 and editor of The New York State Constitutional Convention Clearinghouse.

Source: Snider, J.H., Opportunity for Reform: Educate New Yorkers on constitutional convention, Albany Times Union, June 11, 2017.