Don’t trust a Constitutional Convention? Then you don’t trust the people

New York State’s Constitution mandates that a question be placed on the ballot every 20 years asking New Yorkers whether they want to call a state constitutional convention. On Nov. 7, this question will next be on the ballot.

In New York, the unique democratic function of the periodic constitutional convention referendum is to provide a mechanism for the sovereign (the people) to bypass the state Legislature’s gatekeeping power over constitutional amendments. This mechanism protects the people’s right to reform their government when the Legislature has an institutional conflict of interest with the people. Examples of such conflicts include issues involving legislators’ incumbency advantage (e.g., legislative term limits, ethics, and ballot access) and the relative powers of the competing branches of government (e.g., judicial, executive, and local).

The constitutionally mandated convention process grants the public three votes:

- Whether to call a convention

- If a convention is called, to elect delegates to the convention

- To vote the convention’s proposed amendments up or down.

Of the three votes, the third is the critical one because it involves passing law rather than agenda setting.

The crux of the difference between supporters and opponents of a convention involves the third vote. The “no” camp argues the people lack the competence to vote in their own self-interest. But it prefers to avoid making this claim directly because doing so would insult voters.

This indirection is achieved by omitting a key fact — the existence of the third vote — while emphasizing the second vote. In combination, this implies that the function of convention delegates is to not only propose but ratify amendments. This sleight-of-hand is effective partly because much of the public assumes that a convention not only proposes but passes laws — just like a legislature does when passing statutes.

When addressing more sophisticated voters who know of the third vote, the focus of convention opponents shifts away from the people’s competence to a vague mistrust of the democratic process, especially special interests’ ability to hoodwink voters. In a political environment where a large faction of the public widely distrusts democratic institutions and believes its opponents are winning (e.g. a Pew Research Center report found that most Democrats think Republicans are winning and vice versa), this can be an effective strategy, provided it is couched in carefully coded language.

One problem with this anti-democratic argument is that it is based on a slippery slope. If the public can’t be trusted to vote on an amendment that comes out of a convention, how can it be trusted to vote on any constitutional amendment or, for that matter, anything at all? If democracy is to be sustainable, the public must be allowed to vote on constitutional amendments. The no camp seeks to avoid such awkward questions by relying whenever possible on one-way communications such as 30-second ads, bumper stickers, and yard signs.

It’s also telling that the no camp, while arguing that the convention could be hijacked by special-interests, is the side spending big on lobbying. According to Politico, groups opposing a convention, mostly unions, spent $10.6 million on lobbying in 2016, while supporters spent $353,585. Who is doing the hoodwinking?

Ultimately, the question of how much to trust one’s fellow Americans comes down to the alternatives. Polls show remarkable contempt for our democratic institutions, including Albany. So do our state legislators, who routinely run for Albany by running against it. However, most Americans also agree that non-democratic forms of government are even worse.

The merits of holding a convention boil down to which of New York’s two types of constitutionally specified amendment processes — one controlled by the Legislature and the other not — is better suited to addressing constitutional reforms where the Legislature has an institutional conflict of interest with the people.

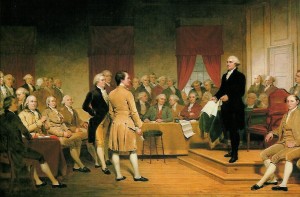

Some of America’s most notable historians believe that as a method of institutionalizing popular sovereignty, America’s invention of the constitutional convention was one of its greatest contributions to democracy’s development across the world. This innovation removed the legislature from the constitution-making process, where lawmakers would have an obvious conflict of interest in drafting law designed to limit their own powers. Since the late 18th century, every U.S. state has institutionalized the convention process as a check on legislative power. It has been used 236 times, including nine times in New York.

The framers of New York’s Constitution didn’t trust New York’s Legislature with gatekeeping power over all future constitutional amendments. Nor should we. When the convention process is disparaged, popular sovereignty is disparaged.

Perhaps democracy really is an unworkable form of government. But until a better alternative is clearly specified and tested, we should stick with democracy.

***

J.H. Snider is the author of Does the World Really Belong to the Living? The Decline of the Constitutional Convention in New York and Other US States, 1776–2015 and editor of The New York State Constitutional Convention Clearinghouse.

Source: Snider, J.H., Don’t trust a Constitutional Convention? Then you don’t trust the people, U.S.A. Today Network, September 13, 2017. The U.S.A. Today Network also published a video version of the op-ed (see below) that they are running in their New York State papers: Trust New Yorkers? Then trust a Constitutional Convention, September 13, 2017.