Post-Mortem: New York’s Nov. 7, 2017 Referendum To Call A Constitutional Convention

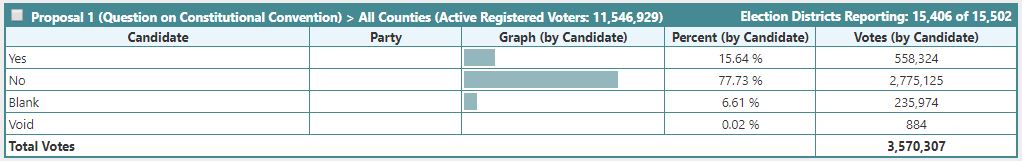

The magnitude of New York’s Nov. 7 constitutional convention referendum defeat was historic. The referendum received only 15.64% of total votes, including blanks, and only 16.75% of yes or no votes (this result was updated on Nov. 10, 2017 after absentee ballots were counted; see New York Board of Elections results below). My database of such referendum election results goes back to 1965. Prior to New York State, there had been 48 such referendums. The lowest percentage of yes to total yes or no votes prior to that was 17.96%—and that was in a state that only 18 years before had changed its constitution via convention and was very happy with the result. So it is indeed remarkable that New York’s convention supporters managed to win so few yes votes.

One of my primary academic interests is explaining the increasingly dismal politics of the periodic state constitutional convention referendum. (See Snider, J.H., Does the World Really Belong to the Living? The Decline of the Constitutional Convention in New York and Other US States, 1776–2015, Journal of American Political Thought.) I thus arguably have a conflict of interest because if the convention call had passed my theory would have been undercut.

However, my theory does little to explain the extent of New York’s blowout. New York’s convention advocates ran the classiest campaign of any among the dozens in recent decades. But the opposition responded with an extraordinarily well-resourced and sophisticated campaign that seemingly left no stone unturned. The “no campaign” acted with the intensity of a threatened mother bear with cubs, and the “yes campaign” like a frightened pack of rodents in the shadow of that mother bear.

The “Yes” vs. “No” Campaigns

The yes campaign won the editorial and op-ed war but badly lost the grassroots campaign, including social media, lawn signs, car bumper stickers, and phone banking. Every New Yorker saw a no sign on a neighbor’s lawn; only a small percentage read the editorial pages.

The yes campaign did well with good government endorsements. But that is an interest group category that has gotten weaker and weaker during the last fifty years. In any case, it was annihilated in the overall category of interest group and incumbent politician endorsements. Explaining the growth of this interest-group and incumbent-politician opposition was central to my academic paper.

On the surface, news coverage was split evenly. Most of it, especially the broadcast TV and radio mass media that most voters watch, did little more than signify that the convention referendum would be on the ballot. Daily newspapers provided more context. But much of it was of the he-said, she-said variety, with the media seemingly plucking out of the ether advocates for the yes and no sides and then presenting their arguments. He-said, she-said news follows the canons of journalistic objectivity but is widely criticized by both advocates and academics for being indifferent to truth and propagating misinformation.

Much of the influence of these news stories had less to do with the arguments presented than who was making them. Here, the “no campaign” won hands down. They were very careful to pick the spokespeople for their public face, and the ones supplying the money and poll-tested arguments were happy to grant them that visibility.

The yes campaign had spokespeople who were by no means slouches. But yes advocates were far less disciplined in both the messages that they sought to convey and the people they promoted to the press as spokespeople. The one-to-one-relationship between money people and spokespeople was far greater among yes advocates. Self-promotion came first; winning second.

Perhaps the greatest bias in the news coverage stemmed from the newspapers’ definition of objective news coverage. There is merit in providing equal news coverage to both sides of an argument. But the newspapers for the most part were indifferent to the truth or falsity of what was said. This gave the side most willing to stretch the truth a significant leg up. New York’s largest newspaper by daily circulation, the New York Times, illustrates the best of this he-said, she-said coverage.

It has been widely reported that local investigative reporting is in decline in America. It is an expensive type of reporting, and for a variety of reasons, including changed advertising markets and the greater ease with which competing newspapers can plagiarize expensive stories (prior to the Internet, papers generally had an entire 24-hour news cycle before competing papers could plagiarize their work), there is less economic incentive than ever before to do it. This election provided a good example of the decline of such reporting.

Also striking was the relative lack of high profile news coverage in the mass media outlets. Those who look at my website with its hundreds of news articles might think otherwise. But The New York State Constitutional Convention Clearinghouse provides no information about the visibility of article placement, and New York is a giant media market with dozens of daily newspapers. Again, the poster child is the New York Times, with its abysmal and low-profile news coverage. In 1997, when this question was last on the ballot, it provided more coverage.

Perhaps the greatest underreported story was the extent to which the unions bullied other groups into either staying out of the fray or joining their opposition coalition. I have already written about this phenomenon in a variety of articles. But here I’ll just mention one: the marijuana lobby. In many states, the marijuana lobby has done well with legislative bypass mechanisms–that is, the popular initiative–and could probably have done well with New York’s different and only available bypass mechanism: the periodic constitutional convention referendum. But the key players in the marijuana lobby view the unions as a valuable financial supporter and critical political ally. The unions made it clear that if the marijuana lobby opposed them in New York they’d get no more support in other states. Given that political reality, the only rational course for the mainstream players was to stay on the sidelines, which they did. There were a few scattered media allegations of retribution (e.g., one of the police unions, via an arrest by uniformed officers, possibly going after Dick Dadey of Citizens Union) but nothing close to thoughtful reporting of the coalition politics that are so central to state constitutional convention referendum politics.

No account of the referendum politics would be complete without a discussion of Bill Samuels, the brilliant, entrepreneurial advocate who personally funded the bulk of the yes campaign and shaped it in his image via nypeoplesconvention.org. In many respects, his achievement was impressive. In comparison to yes campaigns in other states, he assembled an accomplished team, and they produced classy work with a modest budget.

But Samuels had many conflicting agendas. My initial impression was that his primary goal was to win the referendum. But over time I came to have doubts. His was a world of political allies and enemies irrespective of referendum politics. At times, I wondered whether he framed his arguments (and focused his resources) to win as a candidate for convention delegate in his home district—or perhaps to run for some other elected office in his local district. He also wanted to lead a movement of progressives, including government unions, to take on Governor Andrew Cuomo, a conservative Democrat. These competing interests were not well suited to crafting a message that would appeal to a large cross-section of New York.

Samuels’s strengths were also his greatest weaknesses. His team was brilliant at coming up with problems a convention could solve for his political base. But with each problem he solved he may have lost more people than he gained. In contrast, the no campaign stuck to a few focus group tested themes: the high cost of a convention, its redundancy with legislatively initiated amendments, and its high risk.

The Samuels campaign released some 25 videos, but other than the video of Samuels launching his campaign (with almost 4,000 views), none received more than 1,000 views as of November 8, 2017. These videos were posted on YouTube, which provides viewer counts. In contrast, the no campaign tended to post its videos on websites (such as the home page of New Yorkers Against Corruption) that didn’t provide viewer counts. Most notably, its broadcast TV ads provided no viewer information. But when NYSUT, the backbone of the no campaign, ran video just ads for its own members, the ads occasionally received a half million or more views. For more details, see the Clearinghouse’s collection of no campaign video ads.

In terms of strategy, the yes campaign apparently won no converts by ceaselessly arguing during the home stretch–I think disingenuously–that a convention would pose no threat to union pensions. At the very least, the unions showed no signs of believing this argument. Nor have they believed it in other states. My own view, as I argued in one of my 18 op-eds, is that the unions aren’t idiots. When they again and again and again in New York and other states mobilize their members by telling them that a convention would endanger their pensions and then backup their concerns by spending whatever it takes to ensure that a convention referendum doesn’t pass, I believe their concerns should be taken seriously. However, the narrow point the yes campaign focused on–that federal contract law protects existing pension contracts–was fundamentally true even if only a small aspect of the unions’ pension concerns.

There was no love lost between me and some of the local academics who dominated the convention debate in New York. New York was lucky to have such knowledgeable, well-connected, and energetic academic advocates. But there was also a vicious, mutual-backscratching, and self-promoting culture among them that may have backfired. The institutions with which they were affiliated, including various good government groups, cultivated their good favor and promoted them to the hilt. But as we can best see in retrospect, it came at the exclusion of other voices. For several articles I wrote about this culture—albeit somewhat elusively—see here.

As an analogy, I am reminded of the recent Kurdish referendum in Iraq. The Kurdish leadership promoted the referendum with a unified voice and woe to anyone who dissented. Only after defeat could people see their mistake in silencing other voices.

The Underlying Dynamic

All the above micro-variables, however, don’t capture the underlying dynamic of how people voted on Nov. 7. That underlying dynamic is what I tried to explain in the scholarly paper I mentioned above.

The American public has become scared of democracy. For good reason or not, they appear to distrust their fellow Americans’ capacity for self-governance. And they are so distrustful of their democratic institutions that they can easily be led to believe that any attempt to fix them that depends on those institutions will only make things worse. When this miasma of mistrust is combined with near total ignorance of state constitutionalism, they become vulnerable to those who would exploit this toxic mix. The result is a strong bias in favor of the state constitutional status quo—and the interests that thrive under it.

What is responsible for this growing mistrust and ignorance? That is the most interesting question to me.

The Future: A Prediction

My guess is that New York State will now sink into the rut of most other states with the periodic state constitutional convention referendum. If so, yes advocates in 2037 will be so discouraged as to not even try. This, in turn, will contribute to a negative spiral of hopelessness. In the absence of credible opposition, the arguments of convention opponents will then become a self-fulfilling prophecy. Those with invincible power don’t have to even exercise it because the weak won’t dare to challenge it. America and New York will then be ripe for demagoguery because the people will believe that only a demagogue can fix the system.

# # #

For the second in my two-part post-mortem series, see: Snider, J.H., The Advocacy Community’s Culture of “Plagiarism”: A Case Study of New York’s Nov. 7, 2017 State Constitutional Convention Referendum, It’s a Long Way to Constitutional Valhalla, November 9, 2017.

Other Takes on the Defeat

Newspaper Articles

Klepper, David, Convention canned, push for vote on gun bill, Lockport Union-Sun & Journal, November 12, 2017

Hamilton, Matthew, Constitutional convention supporters try a different tack until 2037; Voters overwhelmingly reject once-in-20-years ballot question, Times Union, November 9, 2017.

Mahoney, Bill, Constitutional convention question headed toward landslide defeat, Politico New York, November 7, 2017.

Vielkind, Jimmy, ‘Special-interest money’ scares Cuomo from constitutional convention, Politico New York, November 7, 2017.

New York Voters Reject Ballot Measure Calling For Constitutional Convention, CBS Local, November 7, 2017.

New York rejects constitutional convention, ABC7NY, November 7, 2017.

McKinley, Jesse, New York Voters Reject a Constitutional Convention, New York Times, November 7, 2017.

Blain, Glenn, New York State voters reject constitutional convention, approve proposal to seize pensions of corrupt politicians, New York Daily News, November 7, 2017.

Velasquez, Josefa, Ballot Measure Authorizing State Constitutional Convention Fails, New York Law Journal, November 7, 2017.

Campanile, Carl, and Kirstan Conley, NY voters shoot down constitutional convention proposal, New York Post, November 7, 2017.

New York voters reject constitutional convention, Associated Press, November 7, 2017.

Zremski, Jerry, New York voters nix constitutional convention, vote to reform pensions, Buffalo News, November 7, 2017.

New York Voters Reject Ballot Measure Calling For Constitutional Convention, CBS Local, November 7, 2017.

Runyeon, Frank G., Constitutional Convention and New York’s 2017 Ballot Proposal Results, City & State, November 8, 2017.p

Campbell, Jon, Constitutional Convention: Landslide defeat shows labor union strength, Poughkeepsie Journal, November 8, 2017.

Constitutional convention rejected in New York, WCAX, November 7, 2017.

Other

Statement of Mario Cilento, President, New York State AFL-CIO, November 8, 2017.

Statement of Andrew Pallotta, President, New York State United Teachers (NYSUT), November 7, 2017. See also: Candidates backed by NYSUT locals sweep to victory in elections statewide, NYSUT Media Relations, November 8, 2017. “NYSUT President Andy Pallotta said that, in addition to making more than 500,000 phone calls and distributing more than 400,000 lawn signs….” A similar quote was reported in a Labor Press article.

Statement of Jimmy Conigliaro Sr, Vice President, Eastern Territory, International Association of Machinists, November 9, 2017.

Statement of the United Federation of Teachers, UFT Campaigns, November 8, 2017. See also: Johnson, Stephen, Labor and activists celebrate pushback against constitutional convention, New York Amsterdam News, November 16, 2017: “American Federation of Teachers President Randi Weingarten said New Yorkers ‘voted to protect our rights to a free public education, to join a union and bargain collectively, and to workers’ compensation and basic safety and protections on the job….We voted to protect pensions, supports for seniors and the poor, and the ‘forever wild’ provision of our state constitution that has protected the beautiful Adirondacks and Catskills. All of these rights would have been at risk in a state constitutional convention that would have attracted big moneyed interests who want to strip people of their rights and economic opportunity in order to enrich and empower themselves and their friends.’”

Statement of Barry A. Kaufmann, President, New York State Alliance for Retired Americans, (NYSARA), November 13, 2017.