A con-con is a check on legislative corruption

New York’s state constitution provides for two methods of proposing constitutional amendments — by the Legislature, and by a constitutional convention. Once every 20 years — next on Nov. 7 — New Yorkers are granted the option to utilize the second method.

The second method allows the people to bypass the Legislature’s gatekeeping power over constitutional reform. This right of the people is important when constitutional amendments cover the Legislature’s own power, including its members’ incumbency advantages (e.g., their ethics, term limits, redistricting, transparency, campaign finance, and ballot access) and power compared to competing branches of government (e.g., the executive, judicial, and local).

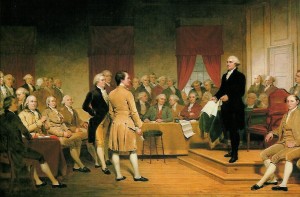

The right of a people to call a convention is one of the few rights widely recognized by the courts to be inalienable, which helps explain why all fifty U.S. states constitutionally sanction this right. America’s invention of the convention has been hailed worldwide as a foundation of modern, constitutional democracy.

In New York, the convention’s role as a check on the Legislature is implemented by granting the public three votes:

• First, a vote on whether to hold a convention. This is critical because legislatures are implacable opponents of constitutional conventions and won’t call one unless forced to. A similar checks and balances problem prodded the framers to mandate periodic elections for the Legislature. In colonial America, a governor could terminate or not call a legislature when it was expected to act adverse to his interests. This made the legislative branch subservient to rather than an effective check on the executive branch.

• Second, a vote for convention delegates. Electing delegates creates a body independent of the Legislature, which would have a conflict of interest proposing constitutional amendments limiting its own power.

• Third, a vote on whether to ratify proposed amendments. This is necessary for both methods of constitutional amendment. Since a constitution embodies the people’s sovereign will, only the people can ratify proposed amendments to it.

Opponents of the upcoming convention referendum have argued that New York already has a constitutional amendment method that can do everything a convention can and at less cost. This is a penny-wise, pound-foolish argument. They are correct that legislatively-initiated amendment is generally less costly, but they overlook the much greater costs of eliminating vital checks and balances. As an analogy, consider the cost savings from eliminating the legislative and judicial branches of government while keeping an executive branch controlled by a single individual. Such cost savings would be dwarfed by the increased costs from the resulting increased corruption and, ultimately, tyranny.

The framers of New York’s constitution were guided by such checks and balances reasoning, which is why they designed New York’s second method of constitutional reform to serve as a check on the Legislature. Today, the fundamental soundness of their vision is best illustrated by the interests of those who disparage it, including the Legislature and the special interest groups that excel at influencing the Legislature.

Convention opponents argue that since legislators and their powerful special interest cronies would dominate a convention, the public shouldn’t call one. But if so, they would be arguing against their own political self-interest, which by their own logic would dictate that they support rather than oppose a convention. Such Machiavellian hypocrisy is like incumbent legislators and their special interest allies who routinely run for Albany by running against it.

Should the people mistrust themselves when voting on constitutional amendments proposed by a state convention? Answering yes is tantamount to giving up on American democracy, which is founded on a written constitution sanctioned by a popular sovereign — we the people — responsible for approving constitutional changes. Accordingly, when the merits of the convention process are debated, the burden of proof should be on those disparaging it — especially when their arguments are formulated, financed, and cheered on by Albany. The fundamental question to ask the naysayers is this: If the people cannot be trusted to approve constitutional amendments, who can?

J.H. Snider is the author of “Does the World Really Belong to the Living? The Decline of the Constitutional Convention in New York and Other U.S. States 1776-2015” and editor of The New York State Constitutional Convention Clearinghouse, which includes a comprehensive collection of ads both for and against a convention.

Source: Snider, J.H., A con-con is a check on legislative corruption, Albany Times Union, October 26, 2017.