11th Hour Barrage: Why Opponents Attack The Constitutional Convention Process—Not Its Substance

On Nov. 7, New Yorkers will vote on whether to call a state constitutional convention. In the lead-up to this election, convention opponents have already spent millions of dollars employing the political strategy known as swift boating, which can mean attacking an opponent’s strengths rather than their weaknesses.

The term entered the lexicon after the 2004 presidential election, when President George W. Bush’s top campaign adviser, Karl Rove, used the method to attack John Kerry, the Democratic presidential nominee. Kerry had a heroic record of military service as the commander of a swift boat during the Vietnam War and the Republican nominee had dodged military service. Rather than concede this point, Rove attacked Kerry’s military service via surrogates who were swift boat veterans.

Most political campaigns focus on attacking an opponent’s weaknesses rather than their strengths. But attacking an opponent’s strengths can be more effective in low-information environments, such as in the last few days before an election when the public has the most trouble sorting through competing claims.

Given the public’s minimal knowledge of state constitutions in general, and constitutional conventions in particular, swift boating has proven to be a shrewd political strategy in the 14 states, including New York, that have a periodic constitutional convention referendums. Most Americans, including reporters, learn nothing in school about their state constitutions, let alone their state constitutional conventions. They’ve not read their state constitution or experienced a convention in their lifetime, and they may not even know they have a state constitution. Convention opponents exploit this knowledge deficit, most notably during the last few weeks before a convention referendum, when they launch a blizzard of negative advertising built on a swift boating strategy.

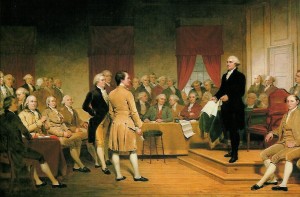

The framers of the New York Constitution designed the periodic convention referendum as a check on the state Legislature, specifically, as a mechanism to bypass the Legislature’s veto power over constitutional reform. They implemented this check by granting the public three votes over the convention process: to call a convention at periodic intervals, to elect delegates to a convention and to vote up or down any amendments a convention might propose.

RELATED: Why foes of a con con have the upper hand

Consider the following swift boat claims and the responses that I believe the framers would have if they were still alive and could defend their work.

Swift Boat Claim: A convention would open a Pandora’s box.

Framers’ Response: An unlimited convention, the claimed Pandora’s box, is a design feature, not a bug, because we designed the periodic convention referendum to provide a way to bypass the state Legislature’s veto power over constitutional amendments. If a legislature could limit a convention’s agenda, it would defeat that purpose.

Swift Boat Claim: A convention cannot do anything a legislature cannot.

Framers’ Response: We designed the New York Constitution to provide for two modes of proposing amendments: one by the state Legislature and the other by convention. The reason there are two and not one is that we designed each to serve a different function.

Swift Boat Claim: The same legislators who control the state Legislature would control a convention; so convening one would be a complete waste of taxpayer money.

Framers’ Response: Not so in our day and not so today. American states have convened 236 conventions, including nine in New York, since 1776. The reason the convention process is now part of all 50 states’ constitutions, and viewed by courts as an inalienable right of the people, is that it is independent of a legislature, which would have a blatant conflict of interest if granted exclusive power to propose limits on its own constitutional powers. In our design, we trusted the people for good reason. No convention called via periodic referendum during the 20th century has had incumbent state legislators constitute more than 10 percent of its delegates. The people understand that electing legislators as delegates would defeat the purpose of calling a convention; consequently, most incumbent legislators won’t even run.

Swift Boat Claim: As indicated by the “no” coalition’s name, New Yorkers Against Corruption, powerful special interests will have even more control over a convention than the state Legislature.

Framers’ Response: We granted the public three votes over the convention process to check, not enhance, legislative corruption. Our sound basic design is illustrated by the fact that powerful special interests – those with a demonstrated track record of successfully influencing legislatures – consistently oppose conventions because they have less control over them. For example, in 2016, those opposing the convention spent 400 times as much as supporters ($13.7 million vs. $35,800) on state candidates, parties and super PACs. In contrast, good government groups support conventions because state legislatures won’t pass popular democratic reforms, such as independent legislative redistricting.

The opposition’s swift boating strategy focuses on a convention’s process rather than the agenda. Thus, it can avoid debating unpopular policies its members want to protect, such as assault weapon protections (New York State Rifle and Pistol Association), government pensions (New York State United Teachers) and abortion (New York State Right to Life). It can even express great sympathy for the good government community’s popular reform agenda (ethics, redistricting and term limits reform) while denigrating the democratic process that would enable that agenda.

If he were alive today, Niccolò Machiavelli, the 16th century diplomat who famously explained the political logic of asymmetric information between rulers and the ruled, might admire the opposition’s skilled use of swift boating. But Machiavellian politics denigrate the democratic process, which is why public officials in democracies never publicly endorse them. The silver lining is that such politics are risky, for when they are publicly exposed, a backlash ensues.

J.H. Snider is the author of “Does the World Really Belong to the Living? The Decline of the Constitutional Convention in New York and Other U.S. States 1776-2015” and editor of The New York State Constitutional Convention Clearinghouse.

Source: Snider, J.H.,11th Hour Barrage: Why Opponents Attack The Constitutional Convention Process—Not Its Substance, City & State, October 23, 2017, pp. 20-1. Republished as Dueling Experts, Part II: The Pros and Cons of Con Con, October 25, 2017.