The Historical Antecedents for New York’s Con Con Debate

When New Yorkers decide on Nov. 7 whether to support or oppose calling a constitutional convention, the only mechanism for the people to bypass legislative opposition to popular constitutional reforms, they want to know how this democratic institution has worked in the past. As the famous aphorism goes, “those who do not learn history are doomed to repeat it.”

But what is the appropriate history to learn? During the past year, convention opponents have argued – usually without bothering to justify their claim – that it was New York’s last convention in 1967. Between now and Nov. 7, they are likely to spend many millions of dollars on ads promoting that claim.

Given the political importance of the 1967 convention, Politico New York recently devoted a four-part series to explaining what happened there. In its first article, it justified its narrow historical focus:

The experience of 1967 looms large over the debate, because even though the state’s political landscape has changed significantly since then, the ’67 convention is the only one held since the Depression-era convention of 1938, making it the only concrete example of what a convention might look like if it is held in 2019.

This justification, taken directly from the opposition’s playbook, is dubious. Excluding the 52 state conventions to vote on proposed federal constitutional amendments, including two in New York (1788 and 1933), America has had 236 state conventions since its founding, including nine in New York. Arguing that New York’s last convention is the only relevant reference point is like arguing after the Yankees lose a game that they both learned nothing valuable from the loss and will lose every additional game during the rest of the season.

RELATED: Pension issue drives New York’s con con politics

1970 Illinois Constitutional Convention

I suggest a different comparison: Illinois’s 1970 convention. The Illinois convention is a good comparison because it happened at approximately the same time as New York’s 1967 convention. Illinois also includes Chicago, which was then the second-largest city in America after New York City.

For purposes of this comparison, I will use the evaluation metrics used by those arguing that the 1967 convention was a dismal failure. As the Politico series accurately reported, many disagree with those metrics. For example, just because the 1967 referendum was defeated doesn’t mean it didn’t contain many excellent provisions, many of which either were later incorporated into New York law (such as its Freedom of Information Law, although the version that passed exempted the state Legislature) or are still sought by good government groups (such as a redistricting commission independent of the Legislature). It also dramatically reduced the length and increased the readability of New York’s exceedingly long, stylistically inconsistent, and amendment plagued constitution, much of which had been made obsolete by changes in federal law (federal law trumps state constitutional law). But here I want to use the opponents’ metrics to argue that the Illinois convention was a success.

The most notable rap against New York’s 1967 convention is that it bundled all its proposed amendments into a single amendment that the voters then rejected, thus implying that the convention was a waste of taxpayer resources. In contrast, Illinois adopted the more common method of bundling non-controversial amendments into a single amendment and unbundling the controversial amendments into separate amendments. The voters then passed the non-controversial package of amendments while defeating most of the controversial ones. The convention cost $3 million in 1970 dollars; $19 million in 2017 dollars.

Another criticism of the 1967 convention is that its delegates included too many state legislators and thus merely mimicked the Legislature’s politics. The implication is that this explains why New Yorkers rejected the convention’s proposals. Consistent with this narrative, 4.8 percent (9 of 186) of the convention delegates were incumbent state legislators that would run again after the convention. The comparable figure for Illinois was 1.7 percent (2 of 116). Convention opponents would have the public believe that the relevant comparison is the total number of delegates who had ever served in public office (82 percent). But that figure ignores the convention’s unique democratic function in New York as a legislative bypass mechanism. Given that function, the only type of public official that would directly subvert it is an incumbent state legislator seeking re-election.

The 1967 delegates also elected New York’s speaker of the Assembly to serve as convention chair, significantly bolstering the opposition’s stance that the institutional interests of the Legislature had undue convention influence. The Illinois delegates elected a leading advocate for calling the convention. That chair, in turn, was careful not to include any poison pill amendments in the bundle of non-controversial amendments the convention proposed to the voters.

Implicit in the opposition’s current no-holds-barred attack on the convention process is that its opposition to the process has been consistent over time. But support for Illinois’s 1970 convention was vigorous among many of the same interest groups that currently oppose New York’s proposed convention. For example, the general counsel of the Illinois ACLU served as a delegate and championed the convention’s proposed bill of rights that he helped draft. And the head of the Illinois PTA, which had close ties with the Illinois teacher unions, served as executive secretary for the yes campaign and helped get the public schools to distribute millions of ballots to school children on the day before the election.

Other Constitutional Conventions

Other constitutional conventions and constitutional convention eras should also be part of the discussion. My personal favorite is Montana’s in 1972. One of the many things that New York could learn from Montana’s convention is its ban on incumbent legislators serving as delegates.

Then there’s the 1938 convention, which proposed nine amendments and included no poison pills in its non-controversial amendment bundle. That’s also the convention that won the unions the provisions that they now fear another convention would remove. The 1938 convention illustrates convention opponents’ propensity to laud past conventions (where they won) while disparaging future ones (where they fear losing).

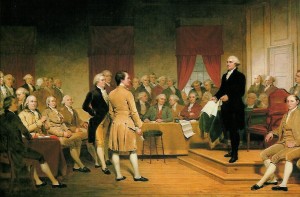

My favorite era of the state constitution is the Founding Era when America invented the convention process. The process they invented, which is now being smeared by opponents, was eventually adopted by all fifty states, hailed by scholars as one of America’s great contributions to the development of democracy worldwide, and ruled by state courts as an inalienable right of the people.

America’s 1787 convention, which proposed the now revered U.S. Constitution, vividly illustrates how opponents can easily find excuses to attack the convention process. Contrary to widely held modern democratic norms, delegates to the 1787 convention were racist (they endorsed slavery and included many slaveholders) and unrepresentative (they disproportionately represented white males in the top 1 percent by wealth). Many were driven by narrow economic and political interests; shirked their responsibilities by missing convention proceedings, drinking excessively, or philandering; and proposed unrealistic good government reforms (such as abolishing slavery). Many anti-federalists claimed the convention’s proposed Constitution would lead to tyranny, not democracy.

* * * *

How could it be that New York has conducted such an infantile debate about relevant historical precedents to 2017’s convention call? I’d suggest that the problem lies not in the opposition, which shrewdly picked the 1967 convention to make its case, but in the narrow-mindedness, narcissism and mutual backscratching culture of New York’s convention advocates, which the press has dutifully reflected (see New York’s Mandarin Constitutional Culture). They have lived in and studied New York, so they naturally talk about what they know best. They have assumed that it isn’t necessary to study conventions in other U.S. states, let alone other countries such as Iceland or Ireland, because New York is the center of the universe. And they have engaged in the intellectually stifling politics of mutual backscratching, which quashes fresh voices.

The next time advocates for or against calling a convention conduct an argument in the media over the merits of New York’s 1967 convention, ask them why that convention is the best point of comparison to the present. After all, learning the wrong lessons from history is worse than learning any history at all. As another aphorism goes, “a little learning is a dangerous thing.”

J.H. Snider is the author of “Does the World Really Belong to the Living? The Decline of the Constitutional Convention in New York and Other U.S. States 1776-2015” and editor of The New York State Constitutional Convention Clearinghouse.

Source: Snider, J.H., The Historical Antecedents for New York’s ConCon Debate, City & State, October 15, 2017.